Online Resource – Welcome

What is this learning resource for?

To provide some useful information about the history of African and Caribbean people in the 19th and 20th Century in Kent.

What is in it?

Some fascinating stories about those who lived, worked and visited the region during the 1800’s and 1900’s. You will learn about the positive contributions they made and much more.

Who helped create the learning resource?

The resource which is made possible with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, has been developed using research from the Black History live project team, which included Sian Drew, Marika Sherwood, Amelia Francis, George Hornby, The Chatham Historic Dockyard, and independent researchers. The concept for this resource was the work of Hamish Tartaglia and Ryan Stone, students at Mid Kent College. We had help from students from Rochester Girls Grammar School who reviewed the site, and Panoramic Design worked with us to upload the content.

What if I need to know more?

We have provided some useful links to other sites throughout the resource. We do not take responsibility for their content, so you should always do more research of your own. We have spoken to a number of historians to help us ensure the information is as accurate as possible.

If there are any errors then let us know so we can change it. The questions have been designed to assist you in your ongoing learning. We aim to keep this resource updated on a regular basis.

Who is this resource for?

This resource is available for anyone to use. You may find it useful as part of your studies, or anyone who has an interest in African and Caribbean history.

We hope you enjoy using this learning resource. If you would like to contribute to updating the resource, email info@macacharity.org.uk.

Introduction

Black people have been present in Great Britain for thousands of years, although it is often thought that Black people are a recent addition to the British population. The latest research about the Cheddar Man, whose fossil remains were found in Somerset a century ago, indicate that 10,000 years ago people living in Britain after the last ice age were dark-skinned with curly hair.

The next earliest historical recordings of Black people in Britain are for the African mounted regiment within the Roman army, which conquered and then ruled England. Some of these men settled here and built families. Then from a recent excavation, we learned of a young woman of North African heritage from the 4th century, who was buried with a great amount of jewellery in York, indicating that she had a high social status. She has been coined the ‘Ivory Bangle Lady’.

Sadly, there exists a huge gap (1,100 years) in research about Black people after Roman Britain until the Tudor era. But the histories that are known to us can be explored and shared until we uncover many more stories! This learning resource celebrates the lives, experiences and contributions of Black people in the Kent and Medway area during the 18th-20th centuries.

For more information on the history of migration in Britain, including the heritage of the Ivory Bangle Lady, click below:

Joshua and Harriet Campbelton

Military

William Brown

William’s birth name is unknown, and she has been recorded in history under the name she used to enlist in the Royal Navy. She was born between 1789-94 and was from the Caribbean Island Grenada, many historians are still unsure about many aspects of her life. Like many other women of her time, William disguised herself as a man to enlist in a profession that was off limits for women.

There is a record of her joining the crew of HMS Queen Charlotte, built in Chatham Dockyard, between May and June 1815 as a landsman sailor, until it was discovered that she was a woman and discharged.

But the 1815 Annual Register painted a much more prestigious account of William, as a 26-year-old woman of African heritage, who had served in the navy for 11 years, spending some time as captain of the fore-top, and beloved by her crew:

“She is a smart figure, about five feet four inches in height, possessed of considerable strength and great activity; her features are rather handsome for a black, and she appears to be about twenty-six years of age… She says she is a married woman, and went to sea in consequence of a quarrel with her husband… She declares her intention of again entering the service as a volunteer”

Q: What more can you find out about women in the Royal Navy? When were women able to serve as officers in the Royal Navy?

For more information, see Joan Grant, ‘William Brown and other Women: Black women in London c1740-1840’, in Women, Migration and Empire. (Trentham Books, 1996)

James Brown

Born in 1783 in Norwich, in 1805 James enlisted as a volunteer for service on board the HMS Victory, the Chatham built flagship of Admiral Horatio Nelson. He lived and worked in Kent as an ordinary seaman. James partook in the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar, one third of those on board the HMS Victory were of Caribbean, African, French and Spanish heritage. So James was just one of the many Black crew members that the Royal Navy were dependent on to maintain its prowess on the seas.

James Brown can be found on the pedestal of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, where he is depicted in action, taking aim with a musket at the Frenchman who shot Nelson. In the aftermath of the battle, James was promoted again to Able Seaman and served on board HMS Ocean, HMS Salvador Del Mundo and HMS Rhin. James is reported to have deserted from HMS Rhin in 1809, and here his historical record comes to an end.

For more information on black seamen at the Battle of Trafalgar, see below:

‘Black sailors in the Royal Navy’, April 2014.

Walter Tull

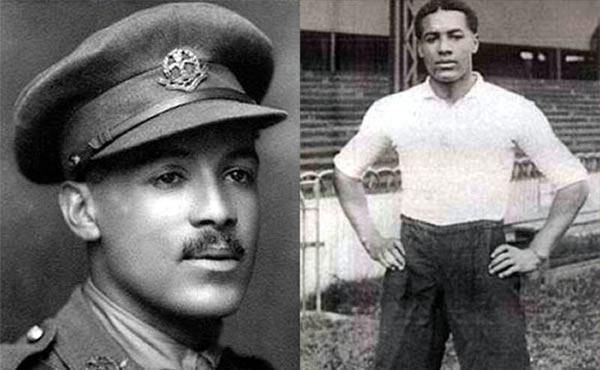

Walter Tull Portrait

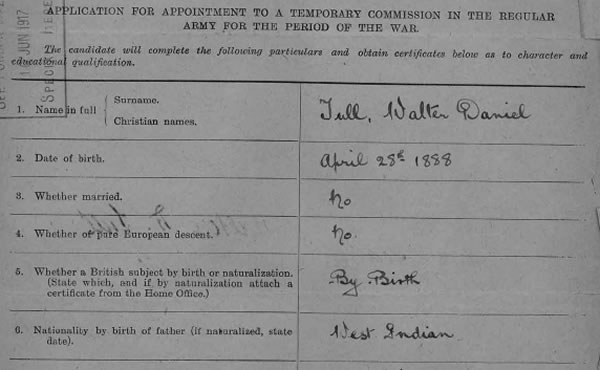

Walter Tull Army Application

Walter Tull is the best remembered as one of the first Black British officers of the First World War. Born in 1888 in Folkestone, his father was a carpenter from Barbados whose own father had been enslaved, and his mother was a local Englishwoman. Walter experienced many hardships in his early life, losing his mother to breast cancer when he was 7, and his father to heart disease three years later.

Walter and his brother Edward were then placed in an orphanage in Bethnal Green, where it is said he developed a thick skin that would serve him well in later life. In 1900, Walter and Edward toured as part of the orphanage’s choir, taking them to St Johns Methodist Church in Glasgow, where Edward was spotted by a couple who would go on to adopt him. Edward became the first Black dentist to hold the licentiate in dental surgery.

With the absence of his brother, Walter found solace in the orphanage’s football team and demonstrated real talent. He began playing for Tottenham Hotspur in 1909 at the age of 21, but racial abuse from football fans and players alike convinced the team’s management to relegate him to the reserve team. Finally, Walter found a star place in Northampton’s first team in 1911.

When war broke out in 1914, Walter was the first of his team to enlist and joined the Football Battalion. He was soon promoted to Lance Sergeant and in 1915 was deployed to France, fighting in key battles such as the Battle of the Somme.

In 1917, despite restrictions against Black people in the British army, Walter became the first Black commissioned officer and was nominated for a Military Cross. But he never received it, as on the 8th March 1918, he was killed in action leading a counter attack in Northern France. Despite the efforts of a soldier under his command, Walter’s body was not recovered.

In recent years, campaigners have been urging the British government and military to grant Walter a posthumous Military Cross and give him and other Black heroes of WWI the recognition they deserve.

Q: Are there any other stories of Black unsung heroes in the military?

Q: What restrictions did Black people face when attempting to enlist to the military in WWI?

For more information about Walter Tull, see: Phil Vasili, Walter Tull, (1888-1918), Officer, Footballer: All the Guns in France Couldn’t Wake Me. (Raw Press, 2009).

Garth Crook’s article about Walter for the Guardian:

BBC4 documentary: ‘Walter Tull: Forgotten Hero’. (2008).

Stephen Bourne: Black Poppies: Britain’s Black Community and the Great War. (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2014).

For more information on the first ever WWI memorial for African and Caribbean service personnel, see:

Political Figures

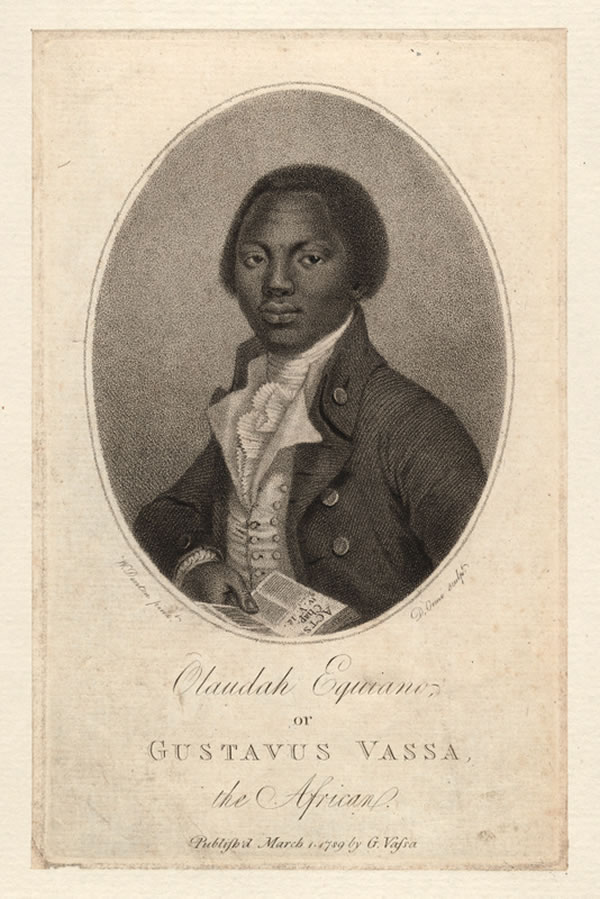

Olaudah Equiano

One of the most influential figures of the abolitionist movement, Equiano stirred the hearts of many and contributed to the successful campaign to end British involvement in the Atlantic Slave Trade. Equiano, born in approximately 1745, had been stolen by slavers at the age of about 11 from his home in modern-day Nigeria, alongside his sister. They were separated, and Equiano was purchased by a Royal Navy officer to work aboard HMS Namur.

He was sold again and placed aboard a merchant ship, but Equiano remained determined to obtain his freedom. By selling products during sailing routes between America and the Caribbean, Equiano managed to save enough money to buy back his freedom. His last owner agreed to grant this at the price he was bought for: £5,000 in today’s terms!

As a freeman, Equiano continued to work aboard ships. In 1773, he partook in an expedition to the Arctic, as a Royal Navy seaman. He also began to raise awareness about the system of slavery. On the 6th of September, 1781, the Zong slave ship left the coast of Africa containing 470 captured African men, women and children.

The ship was well over capacity to maximise profit. But the cramped, unhygienic conditions of the ship led to disease spreading, and 170 captured Africans were thrown overboard, to prevent further spread of disease and to allow the ship owners to claim compensation for ‘lost cargo’ when the ship arrived in Jamaica. Equiano was appalled by the ethics of the Zong case, and he collected evidence whilst working in the Caribbean to present to the influential British abolitionist, Granville Sharp.

Equiano was a member of the Sons of Africa, founded in 1787. The group was made of 12 self-educated Black men and was the first abolitionist organisation led by free Black people. The abolitionist movement was generally dominated by high society white Christians, who had access to newspapers, publications and politicians. As a skilled writer, Equiano compiled his autobiography, entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, and it became one of the most influential pieces of writing for the abolitionist cause (as well as an international bestseller!).

The book is still very popular and has been re-published numerous times. Equiano’s talents as a speaker served him well when he toured his story throughout Britain, awakening many English citizens to the horrors of slavery. Equiano, alongside Granville Sharp, worked with an abolitionist group called the Teston Circle at Barham Court, near Maidstone.

Q: Can you find any other Black people who were abolitionists in Britain?

For more information on Equiano and the abolitionist movement, see below:

Olaudah Equiano

Ignatius Sancho

Ignatius Sancho is believed to have been the first Black voter in Britain. In 1729, he was born into terrible circumstances, on board a slave ship destined for the Spanish West Indies. His mother died soon after, and his father committed suicide in resistance to slave life. When he was two, he was brought to England to work as a servant in Greenwich.

From there, he caught the attention of the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, and they brought him home and gave him a higher amount of freedom and privilege. Ignatius became a lover of writing, reading, poetry and music, and served as the Duchess’ butler until she died in 1751. During the 1760s, Ignatius married Anne Osbourne, a Caribbean woman, and they would go on to have seven children together.

In 1773, Ignatius and his wife bought a grocery shop in Westminster, which became a hub for the great writers, musicians, actors and politicians of the day. He also utilised his writing skills to lay bare the horrors of slavery. He became a close friend of natural rights philosopher, Ottobah Cugoano, who had been formerly enslaved and was a member of the Sons of Africa.

Ignatius published a book entitled A Theory of Music and wrote two plays. He was by this time highly regarded by many as a man of refinery, and was coined “the extraordinary negro”. Due to Ignatius’ status as a financially independent household-owner, he was permitted to vote, making him the first Black person in Britain to do so.

In 1780, Ignatius died due to gout, and became the first person of African descent to receive an obituary by the British press. A collection of letters by Ignatius was published in 1782, in two volumes entitled The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African.

Ignatius Sancho

Q: What made the Sons of Africa such an important group in the abolitionist movement?

For more information on Ignatius Sancho, and the abolitionist movement, see below:

William Cuffay

William Cuffay was an influential leader of the Chartist movement, which fought to gain rights for working-class people in Britain. William’s grandfather had been kidnapped from modern-day Ghana and shipped to St Kitts in the Caribbean. William’s father had been born into slavery there but was able to gain his freedom, although it’s not known how, and worked as a cook aboard British warships.

His father came to Chatham in approximately 1775, where he married a local Englishwoman. William was born in 1788. He grew up to become a tailor and moved to London, where he was met by various losses – his first and second wives both died, and his daughter by his second wife died shortly after birth. Having deformed spine and shin bones, William had his own health challenges throughout his life. He married his third and final wife, Mary Ann Manvell in 1827.

William took up the fight against class oppression in 1834, taking part in a tailors’ strike for shorter working hours. But his political involvement had serious consequences, William was persecuted and lost his job. In 1839, he officially joined the Chartist movement, and became a key leader and organiser, gaining a reputation as one of the most militant people in the movement.

William and others were suspected of planning an underground uprising against the British establishment, and in August 1848, he was arrested and convicted for ‘conspiring to levy war on the Queen’. Like many misfortunate convicts, William was shipped across the world to Tasmania. But this didn’t stop him from his political work. He continued to organise meetings, write articles and inspire younger people around him to become involved in the movement.

William and his wife Mary stayed in Tasmania for the rest of their lives, despite him being granted a free pardon in 1856 which permitted him to travel back to Britain. In 1869, Mary died, and William died a year later at the age of 82 in a workhouse, having gained the respect of countless people as a tireless social activist. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser wrote an obituary for William, that goes as follows: “he always supported the people’s side and opposed everything that tended to cripple the rights of the people”.

William Cuffay

Q: What was a workhouse, and how might people have ended up living in one?

Q: What similar political movements have taken place since the Chartist movement?

For more information on the life of William Cuffay and the lives of his ancestors, see: Martin Hoyles, William Cuffay: The Life and Times of a Chartist Leader. (Hansib Publications, 2013).

For an insight into William Cuffay’s work with the Chartist movement, see below:

Religion

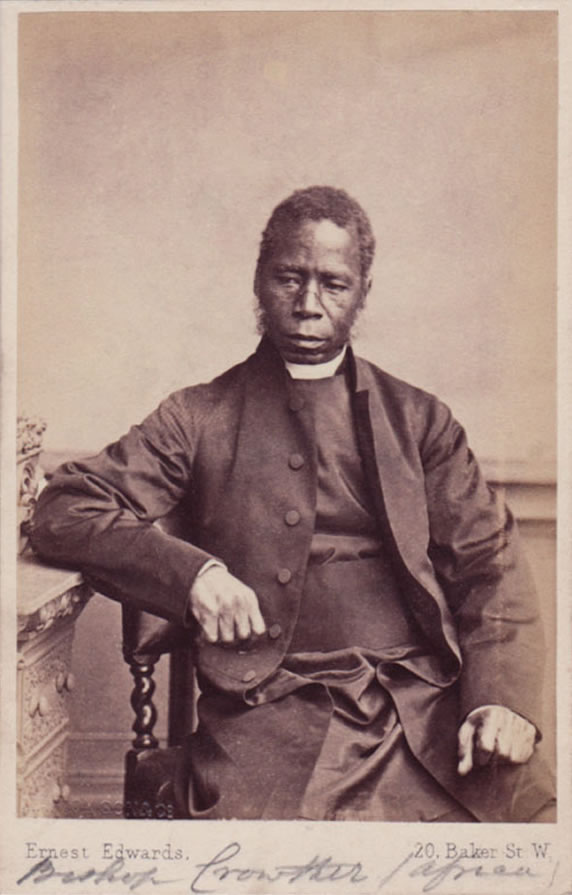

Samuel Crowther

Born in Nigeria in 1807, Samuel grew up to be Britain’s first Black bishop, although his life could have been very different. As a young boy, Samuel was kidnapped by slavers and forced onto a Portuguese slave ship. Fortunately, this ship was intercepted by the Royal Navy, who with the end of the British Slave Trade in 1807, had taken to disrupting other European slave trade endeavours. But the Royal Navy did not take Samuel home, instead he was taken to Freetown, Sierra Leone, a haven for formerly enslaved Africans.

Samuel studied at the Church Missionary Society (CMS) school, where he was a star pupil, and lived in England briefly to complete his education. Him and his best friend, Jacob Schön, were both excellent linguists, studying and recording 500 different languages and dialects that they came across in the very diverse nation of Sierra Leone. Samuel and Jacob undertook an expedition up the river Niger in 1841, which was supported by the British Crown. Jacob then moved to live in Palm Cottage in Gillingham, for health reasons, and Samuel often stayed with him.

On St Peters day 1864, Samuel became an ordained bishop of West Africa, making him the first Black bishop of the Church of England. Samuel died in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1891. His grandson, Herbert Macaulay, would play a major role in gaining Nigerian independence from British colonial rule in 1960.

For more information on Samuel’s career and life, see below:

Can you find anymore Black Bishops in England, since Samuel Crowther?

Samuel Adjai Crowther

Music/Arts

Samuel Coleridge Taylor

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was born in Holborn, London in 1875. His mother was English and his father was a Sierra-Leonian physician. Samuel’s mother had her birth registered in Dover, she then later moved to London. She gave birth to Samuel Coleridge in Holborn, London. Samuel’s parents weren’t married, and his father left for Sierra Leone before Samuel was born, without knowing that his mother was pregnant. Samuel’s name was chosen by his mother after the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who had been a founder of the Romantic Movement.

Samuel’s maternal family were very musically oriented, and after being taught the violin by his grandfather he became a child musical prodigy. At the age of 15, Samuel began learning at the Royal College of Music and picked up composition as his favourite musical format. Samuel grew up to become adored by many music lovers, working as the conductor for the main choir in Rochester Cathedral. Many of his compositions were recorded and are available to listen to today. In 1899, Samuel married fellow Royal College of Music student, Jessie Sarah Fleetwood Walmisley, and they had three children together.

The First Pan-African Congress was held in London in 1900. This marked the beginning of a powerful decade for Black resistance against forms of racial oppression and strong unity between Black people all over the world. Samuel Coleridge Taylor is believed to have been the youngest delegate to the 1900 Congress. At the time of the Congress, Pan-Africanism was a concept practised mainly by African American individuals of a high social class, such as W.E.B Du Bois, the ‘grandfather’ of Pan-Africanism.

Samuel was very engaged with African American community events and toured America three times throughout the early years of the 20th century. But his bright career was suddenly cut short on the 28th of August, 1912, when he collapsed at West Croydon station and died of acute pneumonia days later at the age of 37.

Q: What was the importance of the Pan-African Congress in 1900? How could someone like Samuel have been inspired by it?

Q: Can you name other Black classical musicians?

Q: Can you find any modern day music that has been inspired by historical Black music?

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s compositions are available on YouTube, iTunes, Spotify and other music platforms, e.g:

For more information on the life of Samuel Coleridge Taylor, see: Black Europeans: A British Library Online Gallery Feature by guest curator Mike Phillips:

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

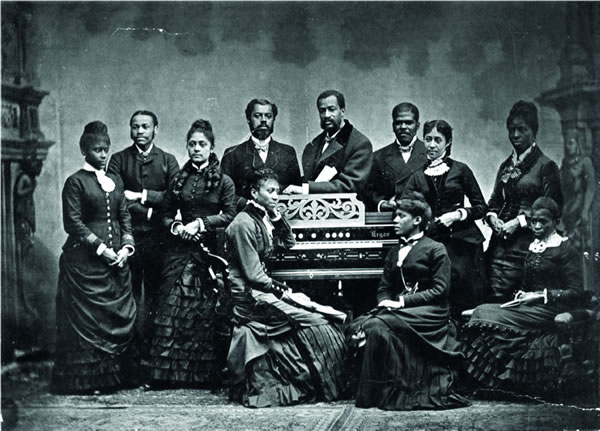

Fisk Jubilee Singers

Fisk University was established as a Black educational institution in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1866. It was firstly named the ‘Fisk Freed Coloured School’, to provide education to African Americans in the aftermath of the American Civil War and the abolition of American slavery.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers still perform today and have toured extensively throughout the world since the 19th century, including in Kent and Medway. In 1873, the Fisk Jubilee Singers toured Britain and Europe, performing to Queen Victoria. The group returned the following year and remained on tour until 1978, raising enough money to build the school’s first permanent building, the Jubilee Hall, which is now a historical landmark.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers have been credited with introducing African American slave songs to European audiences. One of the original members, and the group’s first female leader, Ella Sheppard, was a trusted friend and confidante to African American activists such as Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass.

Fisk Jubilee Singers

Q: Why are the Fisk Jubilee Singers still relevant and popular today?

Q: What more can you find out about the growth of Black Gospel music in England?

For more information on Ella Sheppard, see below:

Notable Local Residents

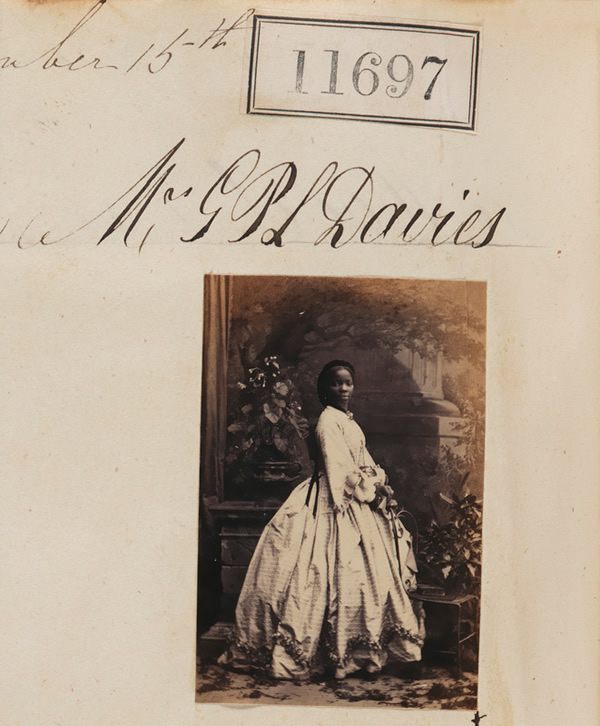

Sarah Forbes Bonetta

Did you know that Queen Victoria had a Black Godchild? Read on to find out more…

Originally called Aina, she was born a Yoruba princess in Nigeria, 1843. At just 5 years old, Aina’s parents were killed during a raid on her village, and she was captured and given to King Ghezo of Dahomey.

Two years later, Commander Frederick Forbes of the Royal Navy saw Sarah whilst visiting King Ghezo during an anti-slavery mission across West Africa. Forbes was concerned that she was intended to be used as a human sacrifice, and he persuaded the king to instead allow him to present Aina as a gift from the “King of the Blacks to the Queen of the whites”.

At such a young age, Aina was viewed by Forbes as an appropriate gift in much the same way a pet animal would be. She was then renamed Sarah Forbes Bonetta and transported to England, where she was presented to Queen Victoria, who was taken by her charm, vitality and intellect.

Sarah suffered from a chronic cough due to the shock of England’s climate and was taken to Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1851. When Sarah was 12, Queen Victoria commanded that Sarah be transported back to England to live under the care of Jacob Schön’s family in Palm Cottage, Gillingham. Sarah was given an allowance from the Queen, and regularly visited her.

When she was 18 years old, Sarah caught the eye of an extremely wealthy Nigerian businessman, James Pinson Labulo Davies, who was living in Britain at the time. At first, Sarah rejected his marriage proposals until she was convinced into accepting after being placed in the care of two elderly ladies in Brighton, whose house Sarah described as a “desolate little pig-sty”. In August 1862, Sarah and James were granted permission to marry by Queen Victoria, and the ceremony took place in Brighton.

The newlyweds moved to Lagos, Nigeria, where Sarah later gave birth to a daughter. With permission from the Queen, Sarah named her daughter Victoria. In 1880 Sarah died in Madeira at the age of 37 from Tuberculosis, and a diary entry from Queen Victoria documented the sad event: “Saw poor Victoria Davies, my Black godchild, who learnt this morning of the death of her dear mother”.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta

In the year of Meghan Markle’s marriage to Prince Harry, and perception of her as the first Black person to join the royal family, it is important to remember Sarah Forbe’s relationship with the Victorian royal family, as Queen Victoria’s “adopted Black child”.

Q: What does Sarah’s story tell you about the Royal Family’s relationship with Africa and African people?

Q: What can you find out about other Black people in the Royal family before Sarah?

For more information on Sarah Forbes Bonetta, see: Joan Anim-Addo. ‘Queen Victoria’s “black daughter”’, in Black Victorians/Black Victoriana. (Rutgers University Press, 2003).

Glossary

Excavation

To remove earth that is covering very old objects buried in the ground in order to discover things about the past

Abolitionist

A person who wants to stop slavery

The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC)

Is a political party whose presence in the South African political landscape spans just over half a century. The PAC’s origins came about as a result of the lack of consensus on the Africanist debate within the African National Congress (ANC): the definition is taken from the following website: